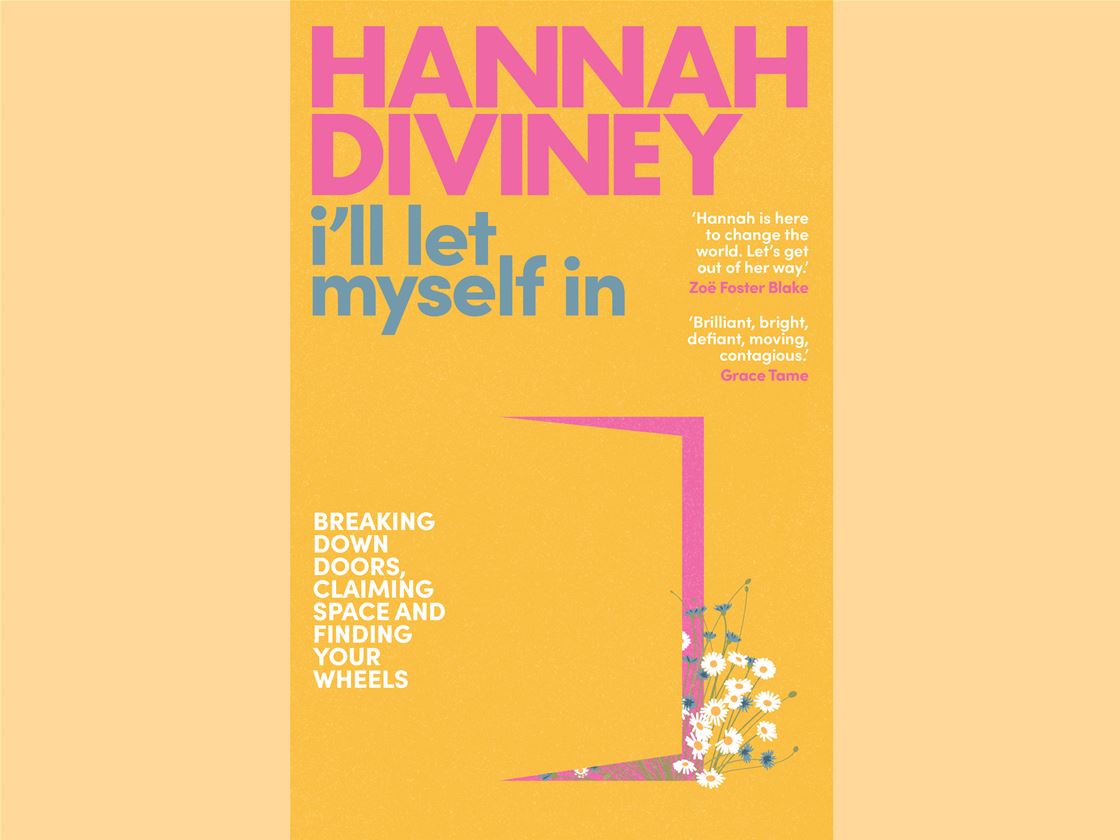

read an excerpt of hannah diviney's memoir

Hannah Diviney is an ace writer and activist who has spoken in-depth about her life as a disabled woman in her recent memoir, "I'll Let Myself In". We've been lucky enough to grab a hold of her 10th chapter for you lucky ducks to read, down below.

If you had asked me at age 13 what I thought I was capable of as a disabled person, I reckon climbing a mountain wouldn’t have made the top 100. And yet there I was, having a conversation in a friend’s kitchen at a Christmas party about doing exactly that.

I’ve since learnt these are the kind of chats you toss around casually when a large chunk of your family friends are people who think doing endurance events, and the weirder the better, is the most fun a human being can have.

It was my curiosity that led me to ask questions about these events. Amused by my interest, one family friend, Mickey Campbell — who has the kind of Scottish accent you need subtitles for the first half a dozen times you hear it — threw it back at me and asked if I’d ever do an endurance event. His suggestion — climb Mount Kilimanjaro. Because obviously that’s the natural place your mind would go.

Mum and Dad were standing behind me, and we all burst out laughing. Yeah, sure, I’ll climb Kilimanjaro. As soon as Wilbur and Babe fly! Once we’d calmed down, Mickey repeated his suggestion — he was serious.

Ever the pragmatist, Mum replied, "How about we try something a little closer to home, with fewer logistics and wild animals?"

He thought for a moment. "How about Mount Kosciuszko?" I stared at him blankly, until he helpfully explained that, like Kilimanjaro, it’s one of the ‘Seven Summits’— the highest mountain on each of the world’s continents — but it’s only five hours’ drive away. Plus, it’s a contained environment: there are no killer animals (minus the occasional snake) and there’s no real danger of being impacted by high altitude.

I shot a nervous glance at Mum and Dad, who seemed to be seriously considering it, and after a bit of playful cajoling—plus the inevitable reminder from Mum that she’s never steered me wrong — I found myself saying yes. On one condition.

If we can make this work, I said, it shouldn’t be just about me. I wanted other kids and people with CP to experience it too, because I was certain they’d never imagine this is something they can do either.

Mickey said that it would make sense for us to use the sheer scale of this challenge to raise some much-needed funds for Cerebral Palsy Alliance, the main organisation for treating CP in New South Wales where I’d been a client since I was the grand old age of twelve weeks. They’d been responsible for helping me access all sorts of services, from physio and occupational therapy to some of my earliest psychologists. I owe them a lot. Without their support, I wouldn’t have the life I do now, nor would I be as well-equipped as I am (there’s always room for improvement) to manage my CP and all its impacts. More specifically, we agreed that whatever we raised — and that was how confident Mickey was, as an experienced mountaineer, that this would work — was to go towards funding sports equipment and programs that would empower young people with disabilities to be active and have a healthier relationship with exercise than I did when I was a kid.

The truth is, I hated exercise. Detested every single second of my monotonous and repetitive physio sessions. All the exercises felt pointless, although arguably functional, designed as forms of torture rather than anything to make me feel good or encourage self-love. In fact, they did the opposite, compounding the insidious belief I secretly held that my body was useless, that it was ugly, that I was broken or somehow worth less than everyone else.

Exercise felt like a punishment for my body, a reminder, perhaps unintentional but still vicious, of all the things I couldn’t do, and of the fact that even the ‘simplest’ of movements for other people felt to me, ironically, like climbing a mountain. So if there was anything I could do to help keep others from ever feeling that way, I would do it.

First, we had to make sure our idea was even remotely physically possible, and that could only be achieved through a practice run. So off we went, Mickey’s family and mine, one summer weekend in February 2013, which was supposedly the best time for climbing the mountain.

On the day we drove down from Sydney, it was 44 degrees Celsius, the kind of shimmering heat that flattens you the moment you step outside. The heat followed us wherever we drove, culminating in what we thought was a glorious walk through the scrubland and paths of the place we were staying. By that stage, thankfully, things had cooled down enough that our skin wasn’t in danger of melting, nor were we at risk of dying by dehydration. Everything was going perfectly. This was going to be a piece of cake!

Yeah, not so much. The next day dawned cold and misty, and I woke to find that my wheelchair had its first-ever flat tyre. It turned out we’d gone over a sharp rock on our casual walk the afternoon before and pierced it. Now what were we going to do? We had nothing to fix it with — could our adventure be over before we’d even begun?

By a stroke of luck, a group of cyclists was staying in the apartment next to us and came to our rescue. It turns out cyclists know a thing or two about misbehaving tyres and had some spare tubes on hand, as well as the necessary tools. Someone was looking out for us that day.

Confused by the weather’s mood swings but buoyed by the allure of the task we were hoping to accomplish, we forged ahead. After all, if we quit whenever something didn’t quite go according to plan or was trickier than expected, I’d have never been out in the world.

The next hurdle? Mickey’s car billowing steam as we drove into the national park. Jumping out of the car, Dad helped him pop the hood to find that some crucial piece of the engine had come loose, and if the car was going to continue to function, it needed to be held in place. Saved by Dad’s unique ability to MacGyver his way into fixing almost anything, on we drove. As if that wasn’t enough, just as we were winding our way through the hills to the parking at the head of the 18.4-kilometre fire trail, it started to rain. And I don’t just mean the spitting and sprinkling that leaves you a little damp but is pretty bearable — no, on this already chilly February day, the heavens opened. We just sat in the car, staring out the window and at each other, all of us frozen for a moment.

Were we really going to do this? Wasn’t the universe making it pretty loud and clear that this was a bad idea? Should we turn back and try for another summer weekend? Surely that was the smart move...

And then Dad’s iPod, which had been playing an eclectic assortment of songs in the background, chose that moment to start blaring Bryan Adams’s rousing rock tune "Can’t Stop This Thing We’ve Started". Through peals of hysterical, incredulous laughter, we decided: that wasn’t the sign we expected the universe to give us, but fair enough!

The gauntlet had been thrown down. We were doing this.

On that first practice run, we only made it halfway up the mountain before being forced to turn back as the weather worsened. We were left soaked and shivering as the rain came in sideways, icy pellets stinging any patch of exposed skin. Our hands shook with cold as we tried to eat or put on more layers. And yet even with all of those challenges, once we were warm, cosy and dry again, the overwhelming consensus was that, yeah, this could definitely work.

Convincing Cerebral Palsy Alliance, however, took a little more work. The three-hour assessment meeting they insisted on is forever burned in my brain. Let’s just say, they weren’t exactly optimistic about our success. But with the CEO and his relentless enthusiasm and his eye for detail on our side, we managed to get them on board. The next few months were a blur of locking in participants, finding corporate partners, raising money and making sure every conceivable logistical problem had a solution.

By February 2014, when the allocated weekend rolled around, I remember being nervous that no one would show up, and yet eighteen teams completed it successfully. The event took over 200 people to run smoothly, the adrenaline high, the serotonin intoxicating. I remember roaring with triumph as that final person crossed the finish line, elated to have raised what I think was about $80,000 for crucial sports equipment, for young people with CP all over the state.

Fast-forward almost decade and we are months away from holding the ninth edition of what we call the Krazy Kosci Klimb, an epic all-expenses-paid weekend away for people with cerebral palsy and their families. It takes over 250 people to put together, as we erect checkpoints, dress up, laugh and dance the night away. It’s changed people’s lives, given them timeless family memories, and created an opportunity for them to get away, which can be rare when accessibility is the exception and not the rule.

But more than all that, it’s given so many people irrefutable proof that disabled people’s lives and our bodies can be full of possibilities never expected by us, our loved ones or the able- bodied volunteers who have their worldviews cracked wide open when they spend time in the midst of our lived experience. For years I’ve spoken at, attended and been told about events designed to help people with disabilities that either raise money or awareness or a mixture of both. The tone is usually one of inspiration, best served with not-so-subtle sides of gratitude and pity. You can almost see the cogs turning in the minds of wealthy guests as the carefully calculated presentation rolls out (pardon the pun) to reveal the cute disabled kid at the centre, whose presence, to put it plainly, has only one real purpose, to pull on the heartstrings — which, it turns out, are often connected to people’s wallets.

But the Klimb plays by different rules. Agency is given back to us, and instead of a carefully curated paragraph, donors get a day right alongside us in real life as we strive to achieve.

Some of the bonds formed on that mountain have led to lasting friendships, changes in career, and a bravery and fearlessness won by achieving something previously considered out of reach. For me, completing the Klimb twice as a participant, and coming back to volunteer almost every year afterwards with my family — as well as being one of the two co-founders alongside Mickey — has given me immeasurable confidence. Without that confidence, I would not be half the advocate I am now.

Not only that, but it’s blasted open the door to so many other things I now consider myself physically capable of.

That’s why, after three or so years of running the event, I said yes to a bigger challenge with the same inherent directive — to prove to myself what I was capable of, and by extension what other people thought too. No, not Mount Kilimanjaro—that idea was still floating in the ether — but a marathon. That’s right, 42.2 kilometres (can’t forget that last 200 metres!) of endurance, athleticism and grit. Simple stuff, really. Except for the part where, you know, I had to make it through 42.2 kilometres.

But completing a marathon was not, in fact, a solo event for me alone. If it relied on me pushing myself, at sixteen years old, I’d probably have been dead after a kilometre, maybe two. In reality, it involved being pushed, mainly by Dad, and then a tag team of family friends who were runners, stationed at various points along the course. The event started in the middle of the city, wound its way over the Sydney Harbour Bridge and finished at the steps of the Sydney Opera House. It also helped that I wasn’t the only participant with CP, as I was joined by a couple of friends and a few new brave souls.

I don’t think I’ve ever actually been quite so grateful to see the Sydney Opera House’s iconic sails as I was the moment we made it over the finish line. Although it might sound like a cushy ride that involved nothing active or apparently strenuous, it turns out doing a marathon in a wheelchair, even when you’re being pushed, is no small feat. Four hours of constant motion made my nausea swell; it genuinely felt like I was on a roller- coaster that I couldn’t get to stop.

My head spun and my stomach ached. I was afraid to eat lest I be sick all over myself and the pavement while other runners were also streaming past. And I really needed to pee. There was no stopping at a portaloo — where would we put the chair? How would I stand? Our flow would be broken, and it would be almost impossible to rejoin without getting trampled. In those first few minutes after the run, with my dystonia in full swing, my relief was almost indescribable.

I’m honestly not sure how Dad and I even made it safely to the bathroom and back, we were staggering and swaying so much. It must’ve looked ridiculous for people passing by, but that tells you how hard these things are. We were left a right mess — so much so that when a friend of ours hosted a celebration at her house, and we discovered that we could only access it via a twisty staircase, I burst into tears.

For all the glory of the marathon and the prestige it brings, the widening of eyes if it comes up in conversation, I don’t think I’ll do one again. Never say never, though. If the right opportunity comes up, even with the myriad anxieties settled in my skin, I will take it. After all, the true definition of fearless is being afraid but doing it anyway, right?

That view of the world has put me in a lot of interesting places, but by far the most euphoric I’ve ever found myself, physically, was at the bottom of a pool with an oxygen tank on my back. Scuba diving was one of the weirdest things I’ve ever done — which puts it in the same league as almost all my best experiences in the last few years. I’m learning to embrace it, but for someone once choked by their comfort zone, its obliteration has been quite the process. When Mum first suggested scuba therapy, I laughed in disbelief — Wait, that’s a real thing? How does it work? But then I got curious — what could the possibilities be? I was raised as a water baby, a necessity for anyone who grows up on Australia’s vast coastline, so I was no stranger to the pool. Many a happy summer memory is soundtracked by the splashing or yells of delight at being launched through the air by Dad in one of his famous ‘Singapore jumps’— so called because they were devised during a swim in a hotel pool in Singapore.

While there were a few rocky years between me and our backyard pool — consecutive summer surgeries will do that to a person — I had also learnt that being in the water was wildly freeing physically. In the pool, I could tentatively shuffle without any real support, arms windmilling like a baby animal learning to balance for the first time. This would generally be followed by a fall onto my back, splashing and spluttering, but the seeds of success were there.

It turned out that scuba therapy — also known as ‘scuba gym’— was several steps above that, though, not least because it involved wearing a huge oxygen tank on your back and a breathing apparatus on your face. I’m not the biggest fan of masks, as I’ll explain. So it was with no small amount of anxiety that I slipped into the water, trying to remember how to breathe in a way I’d never had to think about before.

OK, I’m in the water. What am I meant to do with this weird thing in my mouth? How do I keep it in there? I am also not used to this giant thing on my back — it’s heavy as hell, but hang on a minute...I can balance! Wait, is this what people with normal balance feel like all the time? This is amazing! Ooh, we’re going underwater. OK. All I have to do is step, hold on to someone’s hand and breathe. I can do this.

And I did. In fact, I did it so well, thanks to the calming support of the instructors, that I was able to stand on the pool floor and walk. By myself. Independently. Not holding on to anything or anyone. For the first time in my life.

When I was finished, trusting that the water would guide me, I came up for air, ripped off my mask and burst into tears. When I could speak, it was in a soft voice of childlike awe: Oh, so that’s what that feels like. I’ve been wondering. Even now, a couple of years later, just remembering that feeling as I write, it settles in my chest, pricking tears and shaky breaths.

I hadn’t felt that free since the first time I’d been on the back of a horse, a grey pony called Shadow, who, I was convinced at eight, moonlighted as a unicorn. My adductors were so tight I had to learn to ride without stirrups because my legs couldn’t handle the stretch it would take to reach them. My instructors made that sound cool, telling me that was how the Queen’s Guards learnt to ride before serving her, in case of danger.

Riding was the one place I felt in control, where I felt like maybe my disability wasn’t a disadvantage—that I was actually an equal. As a diehard Saddle Club fan and ‘horse girl’, it was also wonderful for my heart, soul and, it turns out, my sense of balance too. But back to the pool, and the split second my Ghost Kingdom matched my reality.

As you know, my youth was filled with desperate wishes that someone would come and wave a magic wand and ‘fix’ my body. Make it better. Make it likeable. Make it something that did what I asked. Even in moments when I felt or at least thought I should feel good, that little poisonous voice would spew hatred, disgust, pity, fury, as well as snarky, cruel criticism, on an endless loop. But in that moment when I came up from the pool floor and tried to process the magnitude of what the fuck I’d just done, the little voice had nothing to say. It was blissfully silent. I felt a rush of love for my body, which was new and exciting. I didn’t know I could feel that way about it.

Being kind to and about my body has been, and I think always will be, a work in progress for me. There’s too much damage soaked into my formative tissue from all sorts of places for it not to be. But I’m slowly trying to learn that that’s OK too. That while I may never look in a mirror and be entirely satisfied with what I see, or never go through a day without experiencing some sort of frustration for the things my body can’t do, things that are so close and yet tantalisingly so far away, I can breathe.

Sometimes I talk about my body as though it belongs to someone else, because I find it easier to be nice to myself if I pretend I’m a friend and not actually me. Maybe, eventually, I’ll be able to do that for myself too. But hey, at least I’m trying. My body is a vessel. It might do things a little differently, but it still deserves nourishment and encouragement. It’s still strong enough to keep me alive and moving forward, even if it does burn three times as much energy as the average person’s just trying to sit up. It might never work exactly in the ways I want it to, or give me the life so many others have without effort, but that doesn’t mean this life, the one I have — the one

I feel like I’ve fought for — isn’t worth having.

It’d be great if the world at large got that memo. Expect more from disabled bodies, but not in an ableist way. Actually, this applies to everyone — disabled or not. It’s not about whether our bodies can conform to the impossible standards the world seems to have, it’s about whether we can learn to celebrate them, to love them, to stop filling our minds with poisonous loathing for them.

My body’s done some amazing stuff in 24 years, from the wild to the beautifully ordinary, and I bet yours has too. Let’s see what else we can get up to, hey? Watch this space.

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)