a tale of parenthood and mental illness

"From very early on, I tried to articulate my feelings when I looked scary. It took a lot of practice."

My mother had a panic attack on the side of the road. I remember because I was late for school. She might even have indicated before she turned, hard, against the footpath. The car veered sharply. The wheels crunched as they connected with the kerb.

We sat there for some minutes, me and my little brother and little sister, watching as our mother beat her face against the steering wheel. She’s dying, I thought, in my nine-year-old voice, certain there could be no other reason for the way her breath leapt into the windscreen, the way her hands shook and clawed red streaks in her skin, and the way she eventually wound down her window and screamed. She’s dying, I thought, and it’s my fault.

In the early ’90s, no one talked about panic attacks. Maybe no one knew what they were. Just: a big wave comes crashing over your body and tries to drown you for no reason. Or: there’s an earthquake but it’s inside of you and all the people in your brain are falling into the fire pit that’s opened up below. Each time my mother panicked, I assumed she was dying. She didn’t explain it. She probably didn’t have words for it. In those days, the only way to talk about mental illness was to nod solemnly and say “Princess Di” while having something called a “nervous breakdown”. Without knowledge or evidence to the contrary, I could only conclude that my mother was in the process of taking her last breaths.

My own first panic attack happened at around the same time. It was a school day, and I was in class doing gluing or readers or teasing Sam for picking his nose, and then I was dying. I slid right out of the world into another different world contained inside a cellophane wrapper. Air – that good air, the kind I needed for breathing – was torn from my lungs and I ran into the playground and hyperventilated until someone came to find me.

I was dying, too. Obviously. For a decade, my child self battled against an invisible enemy no one would explain to me. Every day, I felt certain I would shoot off the planet and into the sun, and my fried corpse would be stranded there for the rest of time. Every night, I thought about the inevitability of my death, and how I would eventually lose all the people I loved, and how history would cease to exist. That is the kind of child I was, which will come as no surprise to anyone who has met me even in passing.

But this is a story about parenting.

I was 20 when my first child was born. From the moment I found out I was pregnant, people reminded me to doubt my parenting ability. I was too chaotic, too unpredictable. I could barely take care of myself, my panic-riddled brain and depression-laden bones. How would I take care of somebody else? In the maternity ward, a midwife was so certain I couldn’t be responsible for a whole other human that she demanded the name of my non-existent social worker and shouted at me when I wouldn’t give it to her.

And it’s true; I did have gnarly postnatal depression. When my second child was born, when I was 22, I was so tired I could have plucked my eyeballs from my skull without even noticing. But there was a sense of something growing in me. A memory of being on the side of the road with my mother, wondering if the three of us kids were strong enough to drag her body home.

I decided then: I would talk to my children about mental illness.

From very early on, I tried to articulate my feelings when I looked scary. It took a lot of practice. Years of running my double pram from a store because the walls were caving in, or shouting at an invisible man, or shrieking down an empty phone line. I know it’s hard to watch. I know I have turned to my kids on more occasions than I can count, wild-eyed, and panted help me for no observable reason. I know they have had to watch me shout at non-specific threats: I can’t, I have to get out, oh no, no no no. And I know these visible symptoms have gotten worse as they have gotten older.

To stop from hurting them – as much as I can, which is not entirely – I have had to learn to do better. I have had to be patient with my mental illness. Behavioural therapies talk about it in terms like ‘riding it out’ and ‘floating’. I have had to find ways to identify anxious thoughts and articulate them while they were happening, so I could protect my children from blaming themselves. Now, when I’m having a panic attack, I can pull it together enough to say to them, “Try not to worry. I’m not in danger; my brain just thinks I am.”

I have tried to find enough internal fortitude to say, “You’re safe.”

It’s been a two-way learning experience – inadvertently, they have also learnt what to look for in me. I don’t want them to do this but I suppose it is inevitable. They are both wildly empathetic. Sometimes I’ll be driving along and the road will suddenly look far away, and my breath will quicken and my heart will race, and everything inside me will want to burst out and SCREAM I can’t do it! and a little hand (that’s now almost an adult hand) will reach over and hold mine. Just this morning, my now 16-year-old offered me her ‘bad vibes ring’ so I could drive to school without hurtling into space. And I thought: What will your therapist say? and How much is this going to cost me? And I thought: I’m so sorry.

For nearly 20 years we have done this. Not me banging my head against the steering wheel and my children watching to see if I die, but the three of us figuring it out together. And while there are times the guilt overwhelms me, on balance, mostly I think, thank you.

Not just for bringing me back to earth in the impossible moments, but for all the other joy besides.

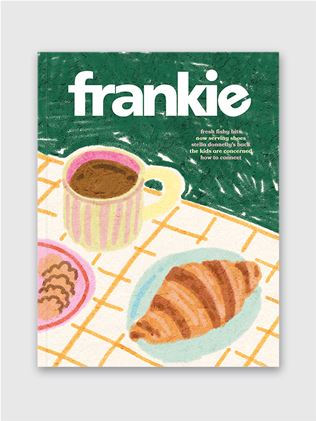

This story comes straight from the pages of frankie feel-good, a one-off issue dedicated to mental health. Head here to pick up a copy.

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)